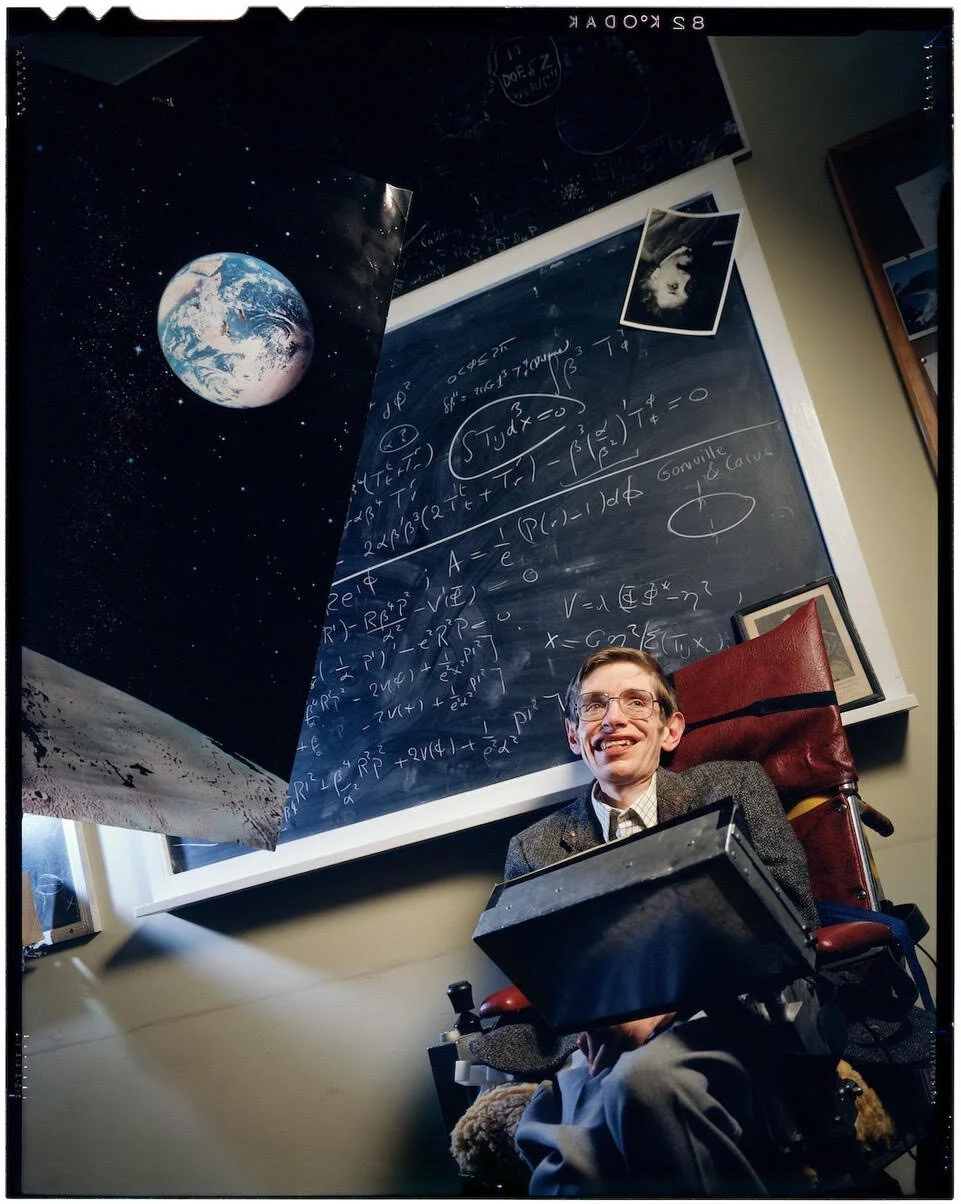

A Brief History of Time - The Photo

If you were asked to picture Professor Stephen Hawking, there’s a good chance you’d actually be thinking about the portrait below shot by British-born photographer David Gamble.

MORPHY | MINT No.1

Professor Stephen Hawking

X

David Gamble

Edition 1/1

THE SINGLE MOST IMPORTANT & ICONIC PHOTO EVER TAKEN, OF THE MOST ACCOMPLISHED THEORETICAL PHYSICIST OF OUR TIME.

Includes exclusive never released mp4 audio file of an uncut, 53 minute interview with photographer David Gamble embedded as an unlockable file for the NFT owner.

Cover of Hawking’s seminal work, “A Brief History of Time” & The first full page image ever printed in Time Magazine